Why private capital keeps backing parts of UK construction but avoids others

The UK construction sector is often described as underinvested. Our analysis of private equity (PE) in the sector suggests that diagnosis is only partly true.

PE has not retreated from construction. Instead, it has become highly selective, backing specific parts of the value chain while consistently avoiding others. This pattern is not anecdotal and is rooted in the underlying economics of different construction business models.

The issue is not whether private capital likes construction. It is which construction activities are structurally investable.

The myth worth challenging

Much of the debate around construction investment starts from the same premise: demand is strong, policy intent is clear (persistent regulatory bottlenecks notwithstanding), and yet capital is reluctant to engage. This is often framed as a failure of confidence or a cyclical response to market uncertainty.

However, the evidence suggests capital allocations in construction is uneven rather than being universally scarce: private equity (PE) is active across building services, compliance-driven activities, facilities management, and specialist distribution. At the same time, PE appears structurally cautious around main contracting, volume-driven factories and housebuilding, and delivery-led models with high working capital and other balance sheet exposures.

How private equity actually looks at construction

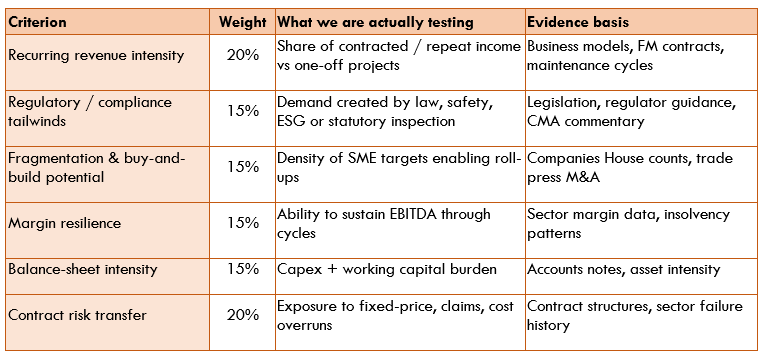

PE firms do not invest in “construction” as a sectoral label. They invest in cashflow characteristics, risk transfer, and scalability. Construction-related opportunities are screened against a small number of recurring questions:

- How repeatable are revenues, and how visible is forward order book?

- To what extent is demand driven by regulation or statutory compliance?

- How fragmented is the market, and can growth be achieved through consolidation?

- Are margins resilient through cost inflation and market cycles?

- How capital-intensive is the business, and how volatile is working capital?

- Where does contract risk actually sit (e.g fixed price delivery and claims risk)?

These questions matter more than whether a business is labelled “contracting”, “manufacturing”, or “technology-enabled”.

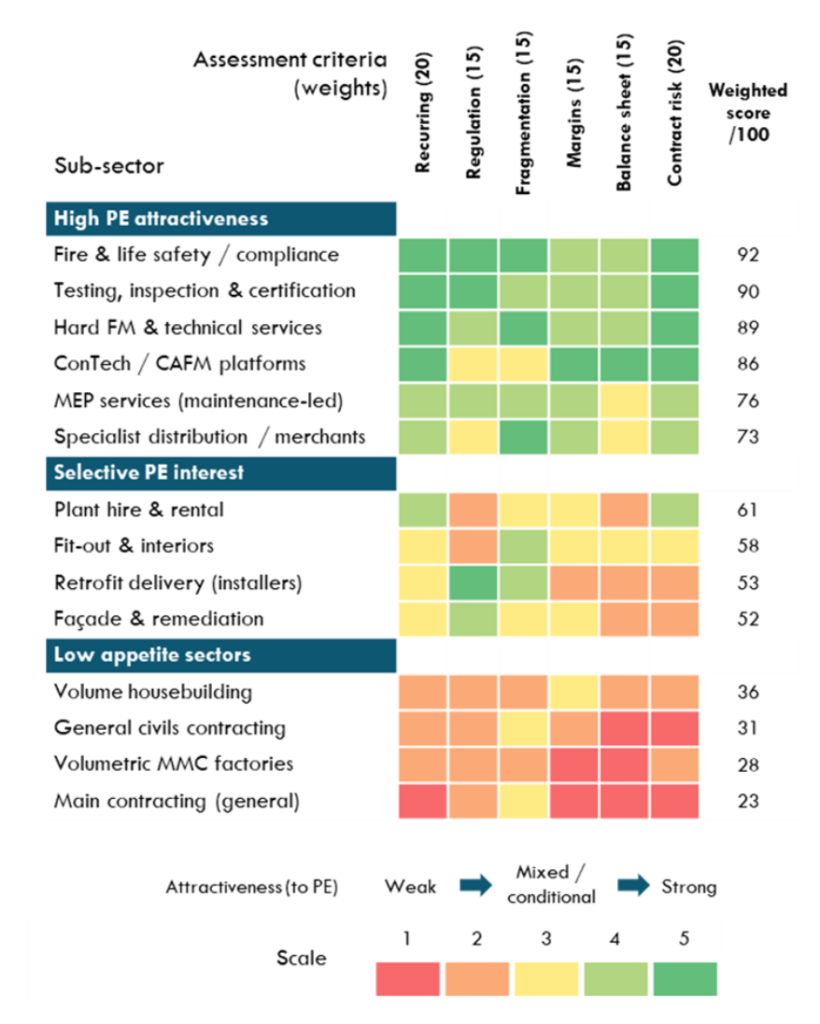

A clear pattern emerges when UK construction sub-sectors are assessed against these investment criteria (see Exhibit 1):

- Private capital appears to cluster around activities that behave more like services platforms than delivery vehicles. These are businesses where revenue is repeatable, compliance creates non-discretionary demand, and risk is contained contractually rather than absorbed on the balance sheet.

- Sectors dominated by fixed-price delivery risk, high upfront capital intensity, and volatile working-capital cycles consistently score poorly, regardless of how strategically important they may be to national objectives.

This evidence suggests these are structural effects rather than cyclical ones.

Exhibit 1: Attractiveness of UK construction to private equity heat map

Notes: ConTech (Construction Technology); CAFM (Computer-Aided Facilities Management).

The framework separates structural attractiveness from market noise. Each criterion is observable through public filings, deal commentary, regulator activity, and sector performance data sources. (Scoring weights and criteria are discussed in the appendix).

Source: Misca Advisors analysis

Why services consistently outperform delivery models

Fire and life safety services, hard facilities management, MEP maintenance, inspection and certification, and specialist distribution all share a common feature: they decouple value creation from project delivery risk.

Service-led construction activities share several common features. Revenues are repeatable, often contractually secured, and frequently underpinned by compliance or asset-lifecycle requirements. Risk is managed through service agreements rather than absorbed through fixed-price delivery.

This allows capital to be deployed towards:

- Scaling operations

- Consolidating fragmented markets

- Investing in systems and management

- Cross-selling complementary services

In contrast, main contracting and volume-driven manufacturing remain exposed to:

- Fixed-price risk

- Margin compression

- Insurance and liability uncertainty

- Utilisation risk

- Weak downside protection

Even where demand is strong, the underlying economics remain fragile. Capital responds accordingly.

Why this distinction matters

- For contractors and specialist services firms: The analysis goes some way in explaining why some businesses attract sustained investor interest while others do not. Size and/or reputation alone doesn’t matter. Where risk and cashflow sit within the operating model are important factors in investment allocations.

- For building product manufacturers: The challenge is not demand visibility but investability. Without mechanisms that address utilisation risk, balance-sheet exposure, and offtake certainty, capital will remain cautious, even where policy intent is clear.

- For investors and lenders: The service-delivery divide clarifies why certain construction related businesses consistently outperform expectations, while traditional delivery models struggle to generate acceptable risk-adjusted returns.

- For policymakers: If private capital is expected to play a meaningful role in delivering housing, retrofit, and infrastructure, the issue is not ambition. It is whether delivery models align with the way capital actually assesses risk.

The implication

Private equity’s behaviour in construction is not a vote against the sector. It is a signal about how construction businesses need to be structured to attract capital. Understanding that distinction is critical for businesses seeking to scale delivery in a capital-constrained environment.

Appendix: Scoring criteria and weights

Note: Contract risk is heavily weighted because it is the single biggest reason PE avoids large parts of construction.

References (latest available, incl. 2025)

British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (BVCA) (2025) Private equity and venture capital investment in the UK: 2024 review and 2025 outlook. London: BVCA.

Companies House (2025) Company accounts, ownership filings and Persons with Significant Control (PSC) registers. London: UK Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/companies-house.

Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) (2021–2025) Merger decisions relating to construction, facilities management and building services. London: CMA. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/competition-and-markets-authority.

KPMG UK (2025) UK construction sector: insolvency trends, risk outlook and capital pressures. London: KPMG.

Moore Kingston Smith (2025) Facilities management and property services M&A insight report. London: Moore Kingston Smith.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2025) Construction output and business demography statistics. Newport: ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk.

BDO LLP (2024) Building products and services: UK sector insights. London: BDO.